It is natural when conducting research to rely, in part at least, on assumptions. Sometimes when the paper trail becomes patchy they are all we have to go on. But these assumptions can sometimes lead us down the wrong path. We are often told that people in Ireland didn’t move around much before the mid 20th century. That if we could trace them to a particular region then there was a good chance they had been there with several generations. However, recent research for clients and into my own family has made me rethink this.

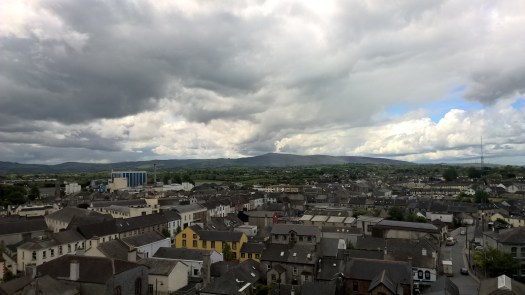

For instance when we receive information from elderly family members we tend to trust it. That information might state the family had been present in that particular area since records began. Of course we’re going to assume this information is correct, especially if we don’t have a reliable paper trail. It makes for a good starting point in our research and can help us get further. Unfortunately putting too much faith in this information can lead to mistakes. Recently I’ve been doing research into a particular branch of my family in Tipperary, prompted by contact with DNA matches on Ancestry. I had information from my grandfather, written down several years ago, giving a year of birth and location for his maternal grandfather. It was within the same parish and seemed plausible so I didn’t see a need to question it. It was only as I went back further and started digging into the parish registers and other records that I began to realise there could be a mistake. A marriage record suggest this individual married into that particular townland. It still places him in the same parish so not a huge deal. However, looking for baptismal records for the year he was born raises questions. The only individual with that name born in that year within the county is listed as being born several parishes over. Not impossible and goes back to assuming people always stayed within the same area. However, when I searched for his death record the age was off. For those born before civil registration was introduced in 1864 sometimes they simply guessed at their age. So that’s not completely reliable either. However, looking at the census records also throws up questions. This individual is listed on the 1911 census as being born in Co. Limerick originally. All of this evidence taken together is too much to ignore and it suggests the information from my grandmother was incorrect. I can understand where the mistake came from. In the days before online research I assume my grandfather or someone else before him simply asked the local parish priest to look into it for them. He found an individual with that name in a nearby parish and assumed it must be them. This is a mistake that any of us can make and frequently do, even professional researchers.

Talking of parish records, another area that can cause confusion when searching on certain websites are the diocesan boundaries. It’s sometimes easy to forget that the boundaries for a diocese don’t always correspond to the county boundaries. So parts of Cork are in Kerry diocese and some parts of Kerry fall within Cork and Ross. Most of North and East Cork is under the jurisdiction of the diocese of Cloyne and a lot of South Tipperary is part of Waterford and Lismore. This also holds true for parishes. Some parishes sit in more than one county, such as Kilbehenny which straddles Tipperary and Limerick. This is especially important if you are searching for records on Roots Ireland. I was puzzled recently as to why my search for baptismal records in South Tipperary wasn’t producing results, until it was suggested I try searching under Waterford. Suddenly I was getting a lot more information. You can check out a map of the various Irish diocese below.

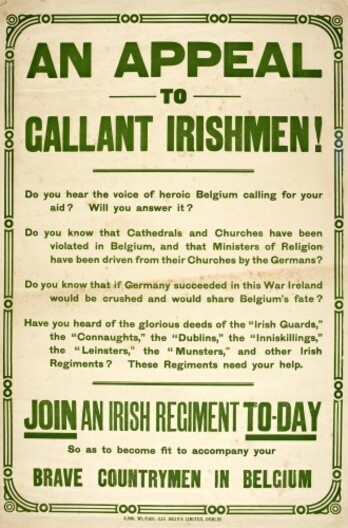

When searching for ancestors we should also keep in mind the upheaval caused by the Famine. When we think of migration, we tend to imagine outward migration, of people saying their goodbyes on the quayside before embarking for a new life in America, Australia or the UK. But we shouldn’t ignore internal migration. The Famine led to depopulation and an availability of land. Should we be surprised that some took the opportunity to take land elsewhere, even if it was just a neighbouring parish?

So the lesson is to never put too much faith in our assumptions. Don’t be afraid to question received information and to independently verify. It might mean disproving long cherished family myths (which isn’t always appreciated) but the whole point research is to know for certain.